"...a tough film that strengthens with the ages"

INDIRECT PAINTING

I recently attended an exhibition of contemporary painting at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. It was billed as an exhibition of "Slow Painting", a term unfamiliar to most and, like most Art terms, one applied most likely in retrospect in order to describe a period or genre that needed a label of distinction. "Indirect Painting" is another term recently and aptly applied to the process. Neo-Realism" is another term sometimes used along with "Modern Realism". These last two make no reference, however, to the technique of painting itself, only to the objective of Realism that I tried to illuminate in my essay on Modern Realism.

"Slow Painting" and "Indirect Painting" imply the use of a multi-layering technique developed over the centuries to take most advantage of the marvelous characteristics of the medium of oil. The nature of the variety of oils used in painting--linseed, walnut, poppy, and others--is that they produce transparent layers of a substance that, unless it is badly polluted, will dry to a tough film that strengthens with the ages and lasts, with care, indefinitely. This is what inspired artists like Van Eyck and DaVinci in the late Renaissance to begin mixing pigments into these oils searching for a better, more expressive medium for painting. This layering process, that begins with what is called an "underpainting" done directly usually without drawing first, because of the drying times between layers, is slow by nature, and artists employing it keep an uninterrupted work flow by working on several pieces simultaneously. Mayer in his Handbook of Artist’s Materials and Techniques says the French term "Grisaille" has been used loosely in this context. The Bullfinch Guide to Art History says that sometimes a grisaille, or Monochromatic Grey painting, was used as an underpainting. To use "Grisaille" in attempting to describe this process in general, however is, I believe, misleading. First of all, in working with the hundreds of period pieces that I have conserved over the last decade and a half, I have never seen a grey underpainting. It is almost invariably done in an umber or sienna, though I have seen black and a few variations in blue. Secondly describing the underpainting alone is insufficient to describe the complete process.

This appears to have been the standard way of painting with oils until the beginning of the impressionist movements in the later 19th century, although many impressionist paintings are done "roughly" in this manner. At that point a fundamental change began in the philosophy of Art Education. Painting academics, which for centuries had taught this slow and "indirect" method, started adopting a "laissez-faire" attitude about Art instruction based on the premise that if one gave too much instruction it would inhibit creativity. Consequently, painting instruction was set adrift in an endless sea of possibilities with no reliable compass, no heritage.

Recently there has been a movement to revive this old technique that has been met with both enthusiasm from some and disdain from others, taunting it as a delaying and uncertain technique. Those employing "fast/direct" painting techniques, which usually means drawing an image and then filling in the colors, like using a highly refined coloring book, even though they are "realists" and claim deep reverence to that tradition, are oddly resistant to the techniques, materials and methods that made the great masterpieces of realism possible. They prefer instead to try to duplicate the look of realism "directly" with modern materials and techniques if possible in a single layer of opaque paint. They then call these efforts "painting" when often in fact they are, more correctly said, illustrating-- brilliantly in some cases to be sure, but illustrating.

To my knowledge, no universally accepted name was ever given to this method of painting during its era, probably because it was considered the standard way of working in oils and needed no special recognition. Very little then was ever been written about it. Indeed, the only specific treatise on the subject from the period that I have ever found was one by Jean Baptiste Corot that I stumbled across in school but have never been able to relocate. In it, as I recall, Corot states that one should use at least 27 layers of paint, going from dark to light, in order to achieve the proper effect.

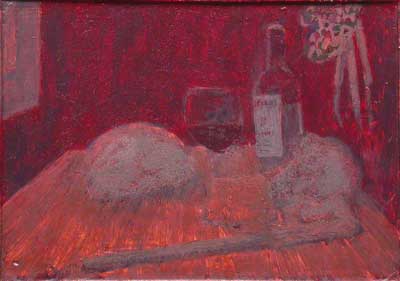

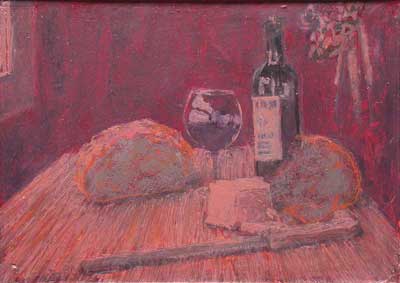

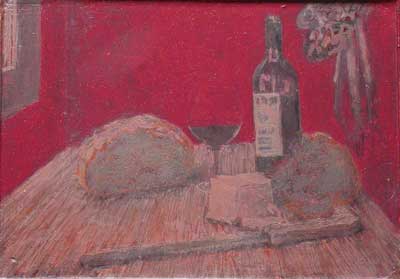

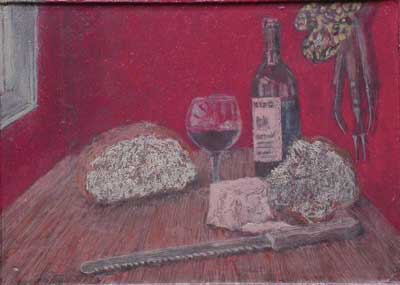

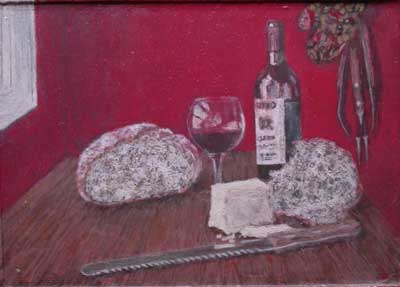

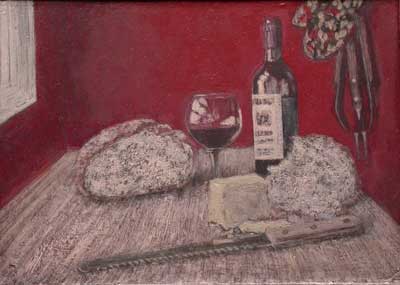

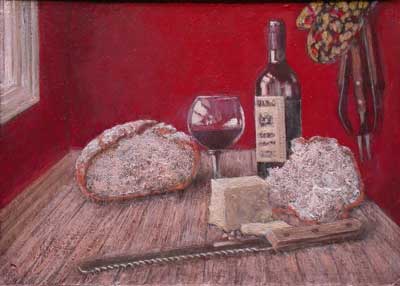

Though the logistics of making a living at painting in modern times is a deterrent to using that many layers of paint, the most success can be obtained by using as many layers as time and budgets permit. I have photographed the process from beginning to end in a series of photographs that illustrate the development of a small painting in this manner and include them here for your edification.

Return to Top of This Page